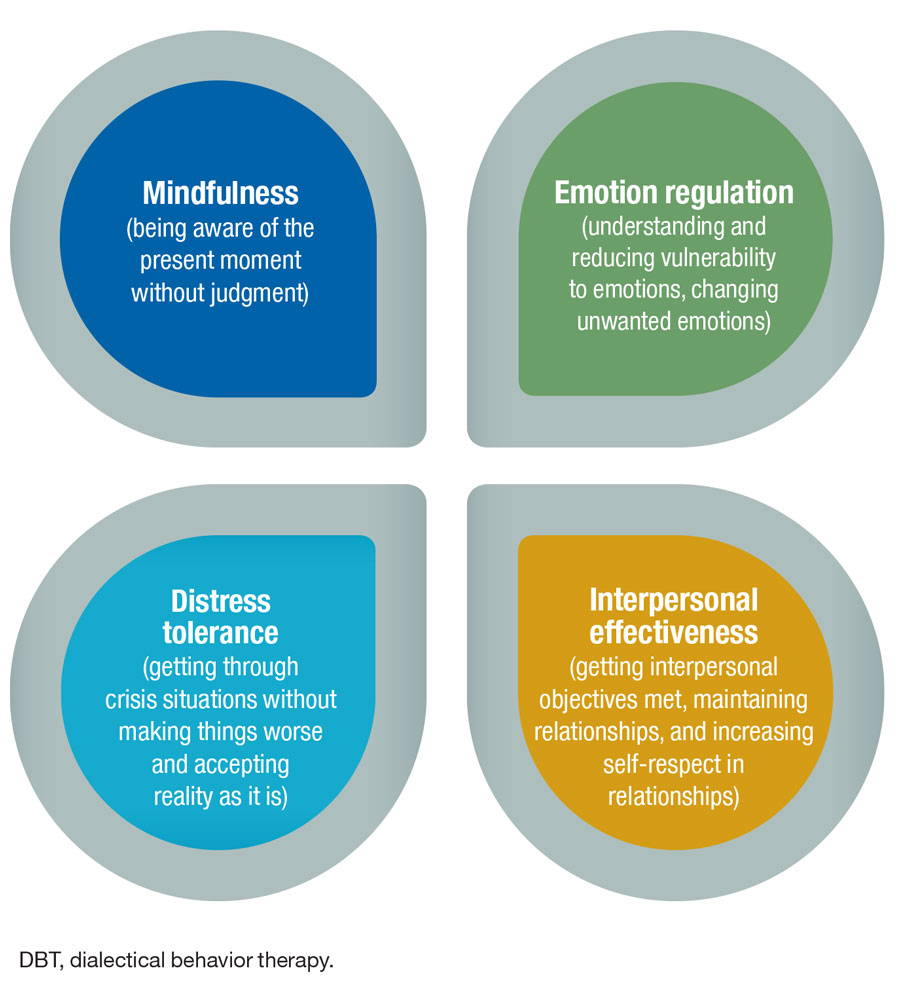

The behavioral health team coordinates behavioral health therapies, including individual or group therapy. During therapy sessions, patients receive non-pharmacological coping skills that include: stress reduction, mindfulness techniques, dialectal behavioral therapy skills and other tools for managing pain.

- Pain Managementdialectical Behavioral Training Reliaslearning

- Dialectical Behavioral Therapy Pdf

- Dialectical Behavioral Therapy For Children

- Dialectical Behavioral Therapy DBT is Part of CBT Dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) is a particular form of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) that is commonly used to treat multiple types of mental health disorders. Often, DBT is used to treat patients with a borderline personality disorder or bipolar disorder.

- PURPOSE Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)–based programs delivered by trained community members could improve functioning and pain in individuals who lack access to such programs. We tested the effectiveness of a peer-delivered diabetes self-management program integrating CBT principles in improving physical activity, functional status, pain, quality of life (QOL), and health outcomes in.

Abstract

Cognitive behavioral therapy programs have the potential to improve quality of life in individuals with chronic pain and diabetes. Rural communities often lack the infrastructure necessary to implement such programs. CBT traditionally requires trained therapists, who are rarely available in these areas. An alternative may be programs delivered by community health workers. We present an iterative developmental approach that combined program adaptation, pretesting, and CHW-training for a CBT-based diabetes self-care program for individuals living with diabetes and chronic pain. Collaborative intervention refinement, combined with CHW training, is a promising methodology for community-engaged research in remote, under resourced communities.

Introduction

Chronic pain is common in diabetes– and has numerous deleterious consequences. Pain is a barrier to self-management, and increases the risk of mood or anxiety disorders, physical and emotional disability, and other poor health outcomes.,– Medications are widely used to manage chronic pain, but they have limited appeal in diabetes due to renal risks of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, liver toxicity of chronic acetaminophen use, and dependence with opioids.– Non-pharmacologic interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), are preferable. CBT-based interventions have been shown to be effective in improving functional status and quality of life for a variety of chronic pain conditions.– These programs feature techniques such as cognitive restructuring, adaptive coping, patient empowerment, skills building, setting realistic and achievable behavioral goals, and stress reduction techniques.19–21 However, they have not been well studied in diabetes and comorbid chronic pain. Furthermore, CBT traditionally requires trained therapists, who are rarely available in rural, underserved areas.

A potential alternative may be CBT-based programs delivered by community health workers (CHWs). CHWs live and work in the communities they serve, so they understand both the barriers to self-management faced by community members as well as realistic strategies to overcome them. In addition, CHWs provide valuable insights regarding their community’s culture, health priorities, and feasibility of program activities, critical knowledge for effective community-based interventions. Increasing evidence supports their use in improving health behaviors in chronic conditions,,– but few studies have incorporated CBT-based programs. Recently, Rahman et al successfully trained CHWs in Pakistan to delivering a CBT-based program, decreasing post-partum depression by 50%. Using this program as a foundation, we developed a CHW-delivered program based on CBT principles to help individuals living with both diabetes and chronic pain to improve their diabetes self-care. In this paper, we present the development and CHW training for this program. The approach we developed may apply widely to interventions in remote communities with high healthcare needs but scarce resources.

Methods

We used a qualitative, iterative approach to development that engaged local community members from the beginning. CHWs with whom our investigative team had partnered in a previous study focused on diabetes management noted that many of their clients were unable to meet exercise goals due to chronic pain.

The setting and CHW selection

Our study was conducted in rural communities located in the Alabama Black Belt region. This region, named for the rich black topsoil, bear excess burden of chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and obesity.27,28 CHWs were residents from several communities in this region. As noted above, these CHWs had worked on a previous diabetes self-management study. Thus, they had nearly 2 years of experience in helping community members with diabetes to set self-management goals and problem solving, using motivational interviewing skills. These CHWs were engaged at the very beginning of the grant, taking part in discussion groups and conference calls to discuss intervention components.

Development of the early draft of the intervention

Based on discussion group data from individuals living with diabetes and chronic pain as well as experienced CHWs in rural Alabama Black Belt communities, we adapted the Pakistani program and combined our existing diabetes self-management program, to specifically address diabetes and chronic pain context. Intervention materials from the Pakistan program were shared with permission to adapt the materials for this study. Discussion groups focused issues related to adapting intervention content, materials, and delivery. The intervention included content around diabetes basics, communication with the doctor and health care providers, healthy eating, physical activity, stress reduction, and social support.

Pain Managementdialectical Behavioral Training Reliaslearning

Intervention pre-testing and CHW training

The 10-week training/pretesting process began with a 6-hour face to face training session. At this in-person session, CHWs selected a training partner for the entire training process. Training included a review of skills such as motivational interviewing, goal setting, assessing barriers, and problem solving. Practicing the skills learned during training was a priority for the CHW training, and we structured the day to provide ample opportunities for roleplaying and practicing skills.

The in-person session was followed by 10 weeks of telephone-based training and certification that also served as a pilot of intervention materials. During these 10 weeks, training pairs took turns roleplaying both as a CHW and as a participant. Although we had not requested this, all of the CHWs decided to complete the daily monitoring and homework tasks that program participants would be asked to do. Because CHWs progressed through the program as both a CHW and a study participant, CHWs were able to provide feedback from both perspectives.

Training, pretesting, and certification process were structured as follows (figure 1). Each week focused on one intervention session and began with a group conference call. Prior to the conference call, the CHWs were asked to watch that session’s educational video, review the accompanying material in the CHW manual, and listen to a model session recorded by the study PI and a staff member. These recordings, which featured the study PI and a staff member modeling the session as a CHW and a participant, were created as each session was brought to the advance draft stage. The scenarios featured in the recording sessions emphasized important content areas and modeled skills that some CHWs were having difficulty mastering during training. During the conference call, the group listened to the model session together, pausing to discuss content, potential emotional moments, and answer any questions. During these calls, CHWs also were asked to provide feedback on the program and to discuss their progress in the training. After the conference call, each CHW practiced the session with their training partner at least two times: once as a CHW and once as a participant. When the CHWs felt ready, a certification call was scheduled.

For CHW certification, we created one participant profile for use in all certification calls (figure 2). While participant goals and interactions that occurred during certification calls differed for each CHW, the participant’s weekly goal attainment and monitoring results were uniform for all CHWs. These decisions were made during a weekly debriefing meeting during which the staff discussed areas that needed further review or special emphasis during the training.

At the beginning of each certification, the certifying staff asked the CHW to comment on what the CHWs liked and disliked about the session’s content (activities and homework; wording and images used during the session), what they found difficult to understand or unfamiliar, and what recommendations they had for changes. Two staff members conducted each certification, with one staff member playing the role of the participant. The second staff member listened to the call to 1) note the strengths of each CHW as well as any weaknesses that need to be addressed during training, 2) determine if the CHW was ready to move on to the next session or needed additional practice, and 3) critically listen to the flow of the session to note any problems and necessary revisions to the program. At the completion of the call, the certifying staff provided the CHW with feedback regarding the CHW’s strengths as well as areas that needed additional work. In the event that the CHW was not certified for the session, the CHW’s community coordinator and study staff worked with the CHW until she was ready to move on to the next session. Upon completion of each week’s certification calls, the study team incorporated CHW recommendations into the intervention sessions and reviewed these modifications with the CHWs during the group conference call. The program materials resulting from the pretesting were given to the CHWs for final review and approval.

Results

Using the method described above, nine community members were trained and certified as CHWs. As seen in table 1, all were females, 9 were African American, 10 had some college or a college degree, and 5 reported an income of $40,000 or more per year.

Table 1

Characteristics of CHWs who participated in the training

| N = 10 | |

|---|---|

| Age, mean, SD | 58.6, 12.6 |

| Female, n | 10 |

| Race, n | |

| African American | 9 |

| Caucasian | 1 |

| Income, n, | |

| <40,000 | 5 |

| ≥40,000 | 5 |

| Some college or college graduate | 10 |

Results of the collaborative intervention development and refinement

Engaging the CHWs early in the intervention development process impacted the final program’s delivery, content, and structure. A key change to the intervention resulting from early discussions with CHWs was the addition of the intervention videos. The original intervention design called for the CHWs to deliver both educational and behavioral content. However, based on discussions with the CHWs, the decision was made to deliver the educational content via videos by content experts such as dieticians, exercise physiologists, and physicians. This removed the pressure from the CHWs to deliver specific health information. The CHWs were able to use the videos as tools during the sessions and focus on their areas of expertise, i.e., providing support, helping participants set and assess diabetes self-management behavioral goals and problem solve barriers, and link participants to community resources.

Another major modification concerned the structure of the CHW manual. Initially, the manual contained bulleted text of the content areas to be covered. However, the CHWs requested a more detailed script, allowing them to either follow the script closely or use it as a guide. This request led to a deeper collaboration between the study team and the CHWs. Not only did the CHWs provide changes and additions to the session script, but they also recommended ways to shape intervention activities to resonate with our target population. Major recommendations and resulting modifications to the program recommended by the CHWs are summarized in table 2. Thus, this parallel training and pretesting process made room for invaluable CHW contributions to program content.

Table 2

Summary of major recommendations from CHWs and resulting modifications.

| Summary of comments | Modifications | |

|---|---|---|

| Program content | Stress reduction was identified as a priority to the community members. | Stress reduction goal was set during session 1 and reviewed during rest of the program. |

| Building a relationship with the client was easier when covering healthy eating and physical activity content rather than communication with doctors. | Sessions were reordered to put healthy eating and physical activity sessions at the beginning of the program. Session on doctor’s visit was moved to session 5. | |

| Several sessions took over 60 minutes. CHWs expressed concern of being able to keep participants engaged over the phone for more than 30-45 minutes. | Content included in each session was reviewed with the CHWs and based on their recommendations, session content and activities were revised to shorten the session. | |

| Program delivery | CHWs expressed concern regarding learning and teaching educational materials to patients | Videos developed with didactic content delivered by content experts |

| CHWs preferred having scripts available instead of bullet points outlining session content | Bulleted content in peer manual turned to scripts |

Description of the final intervention

The final intervention was an 8-session program delivered over a period of 12 weeks. Sessions focused on 6 areas of diabetes and pain self-management: stress reduction, healthy eating, physical activity, social support, medication adherence, and communication with the doctor. Table 3 presents an overview of the program content. All sessions were structured similarly. Each session incorporated that week’s educational messages with 3 general steps: 1) identifying negative or unhealthy thoughts, 2) replacing them with positive or healthy thoughts, and 3) then practicing. Practicing included a discussion of new educational materials covered in the video and several interactive activities reiterating that week’s lesson. These steps were repeated throughout the videos and session activities in the context of each week.

Table 3

| Session | Topic Area | Activity/Homework/Monitoring |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction to program and diabetes basics | Daily Pain and mood monitoring |

| 2 | Stress reduction | Pain and mood monitoring + deep breathing exercise |

| 3 | Physical activity | Pain and mood monitoring, deep breathing exercise + exercise goal |

| 4 | Healthy eating | Pain and mood monitoring, deep breathing exercise, exercise goal + healthy eating |

| 5 | Friends and family | Pain and mood monitoring, deep breathing exercise, exercise goal, healthy eating + goal to identify and engage a healthy buddy to help stay on track after the program ends |

| 6 | Getting the most out of your doctor’s visit | Pain and mood monitoring, deep breathing exercise, exercise goal, healthy eating, getting a list of concerns to speak to doctor and continuing to think about ways to engage a health buddy |

| 7 | Preparing for the future – how to keep going | Pain and mood monitoring, deep breathing exercise, exercise goal, healthy eating, and continuing to think about ways to engage a health buddy Rating program activities and deciding which ones to keep working on after the program ends |

| 8 | Final session – preparing for the future | Pain and mood monitoring, deep breathing exercise, exercise goal, healthy eating |

The participant materials included an activity book, a health-monitoring calendar, and a DVD containing session videos. Prior to a session, participants viewed the session video. Then, they used their activity book during the telephone session and the health-monitoring calendar to complete their homework between sessions. With respect to homework, participants were asked to monitor daily their pain and mood as well as practice daily deep breathing to reduce stress. As they progressed through 12-week program, participants worked with their CHW to add goals related to healthy eating, physical activity, engaging their social network, taking their medications, and improving communication with the doctor. The program concluded with two sessions that prepared the participants to maintain and extend these activities after the end of the program.

Program satisfaction

The success of the combined approach was tangible in the program’s satisfaction ratings by study participants and CHWs. Of the 10 CHWs who began the training, all CHWs completed the training and 9 were matched with participants. One CHW was unable to be matched with participants when the demands of her jobs increased as she was finishing training.

Despite the heavy demands of a CBT-type program, the program was completed by 80% of the intervention participants, and 95% of intervention participants were satisfied or highly satisfied with the program.

Discussion and conclusion

Discussion

We created a model that combined intervention development, training, and pretesting that overcame many of the barriers associated with developing behavioral interventions in partnership with members of remote communities. Although specifically created for adults with diabetes and chronic pain, this model might prove useful for others working in similar remote settings.

Developing novel programs for remote, resource-poor, and culturally distinct communities is challenging. Community participation, ownership, and capacity building are hallmarks of culturally adapted community-based programs. However, limited time, budget, and distance from urban centers, where program developers and trainers are typically based, complicate efforts for collaborative intervention development and training. Providing adequate opportunities to practice skills learned during training is a challenge for any program utilizing CHWs,30 but this difficulty increases in rural settings, where in-person training opportunities are limited by distance, and web-based training is impractical due to limited availability of high-speed Internet connections. Furthermore, intervention fidelity is a major challenge in programs delivered by CHW in remote areas. Creative strategies are needed to make effective interventions available in rural, underserved communities.

Limitations

This training/pretesting combination model does have limitations. This process devotes a sizeable portion of the intervention timetable to program development and training and requires a high level of staff effort. For this study, this effort needed to be flexible as well: our trainers needed to be available during evenings and weekends to accommodate CHWs’ schedules, and staff had to make real-time edits to the intervention as they received CHW feedback and results of the pretest. However, on conclusion of the training/pretesting period, the program was ready for immediate launch. Our training/pretesting combination model also requires a high level of effort from the CHWs over the 10-week training period, with numerous telephone sessions. Nevertheless, of the 10 CHWs that entered the training, all became certified and 9 were matched with program participants.

Conclusion

We developed a training model that effectively overcame the aforementioned challenges. Furthermore, this model combined several steps in intervention development and training that are often done in series, improving program efficiency. Our approach accomplished cultural adaption and intervention refinement, CHW training, and pretesting through a process requiring only one in-person training followed by telephone sessions with between-session practice. Furthermore, the approach had several unforeseen benefits, including empowering CHWs, optimizing team functioning and communication, and resulting in high intervention fidelity during program implementation.

Practice implications

The approach we developed may apply widely to interventions in similar remote communities with high healthcare needs but scarce resources.

Acknowledgments

This study was made possible through grant R18HS019239 from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and departmental funds from the University of Alabama at Birmingham

Thank you to Atif Rahman and Zaeem ul Haq for generously sharing the original program materials for adaptation for this program.

References

Dialectical Behavioral Therapy Pdf

Dialectical Behavioral Therapy For Children